Author: Andrew Berger-Gross

The United States incarcerates a larger share of its population than any other nation on Earth, and recidivism is common: most individuals released from state prisons are re-arrested within two years. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that one of the surest antidotes to recidivism is a good job. In a recent study, we use data from the North Carolina Common Follow-up System to estimate the impact of post-release employment on recidivism. We show that individuals who find work after exiting prison return to prison at a significantly lower rate than their non-employed counterparts, with higher earnings leading to better recidivism outcomes.

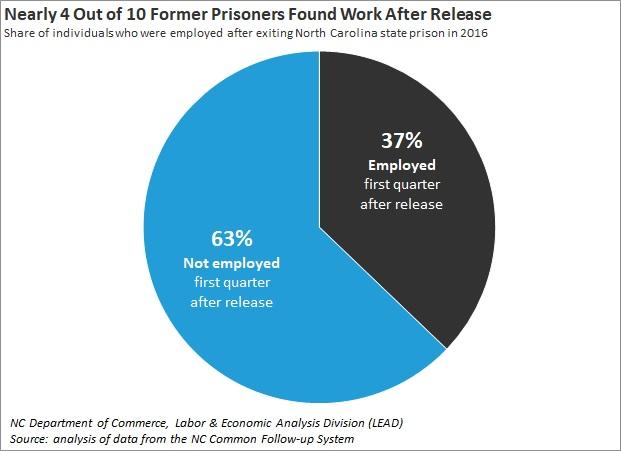

Our study follows 10,861 individuals released from North Carolina state prisons into community supervision in 2016. Of this cohort, nearly four out of 10 were employed during the first quarter (three months) following release [Figure 1].

Employed former prisoners in our sample differed from their non-employed counterparts in ways that may have kept them out of prison regardless of whether they found work after release. For example, they tended to have more pre-prison work experience and a lower prior criminal record level than their non-employed counterparts. We use a statistical adjustment technique that controls for these differences so we can make an “apples-to-apples” comparison between the employed and non-employed groups and estimate the net impact of employment on recidivism. (See the full report for more information about our methodology.)

The effect of this adjustment technique on our findings is illustrated below in Figure 2. Based on the “raw”, unadjusted data on post-prison outcomes, we find that employed individuals in our sample were 26% less likely to return to prison than their non-employed counterparts. After controlling for pre-release differences between the two groups, we find the employed were 20% less likely to return to prison — a smaller impact than indicated by the raw numbers, but still quite substantial.

Our study also shows that the amount of wages earned per quarter has a stronger impact on recidivism outcomes than employment itself. Employed workers in our sample earned a median of $2,707 the first quarter after exiting prison—the equivalent of $10,828 per year on an annualized basis [Figure 3]. Quarterly earnings varied widely in our sample: the highest-paid workers earned more than $5,058 per quarter (or $20,232 per year), while the lowest-paid earned less than $1,020 (or $4,080 per year).

Individuals earning relatively high wages had better recidivism outcomes than their lower-earning peers. The highest-paid workers in our sample were only around half as likely to return to prison, while the lowest-paid returned to prison as often as those who found no employment at all [Figure 4].

The findings from our new study add to a growing body of evidence demonstrating that, although employment is an important pathway out of prison, individuals’ recidivism outcomes can vary depending on whether they find low- or high-quality employment. Finding “any job” after prison may be less important than finding “the right job”. Reentry professionals can help improve former offenders’ chances for success by preparing them for the types of high-quality employment that research like ours has consistently shown to prevent recidivism.

More information about the North Carolina Department of Commerce’s Reentry Initiative can be found here.

More information about the North Carolina Department of Public Safety’s reentry programs and services can be found here.